Anna van der Ploeg

All the bugs in my garden know your name

A new edition by Anna van der Ploeg in collaboration with The David Krut Workshop.

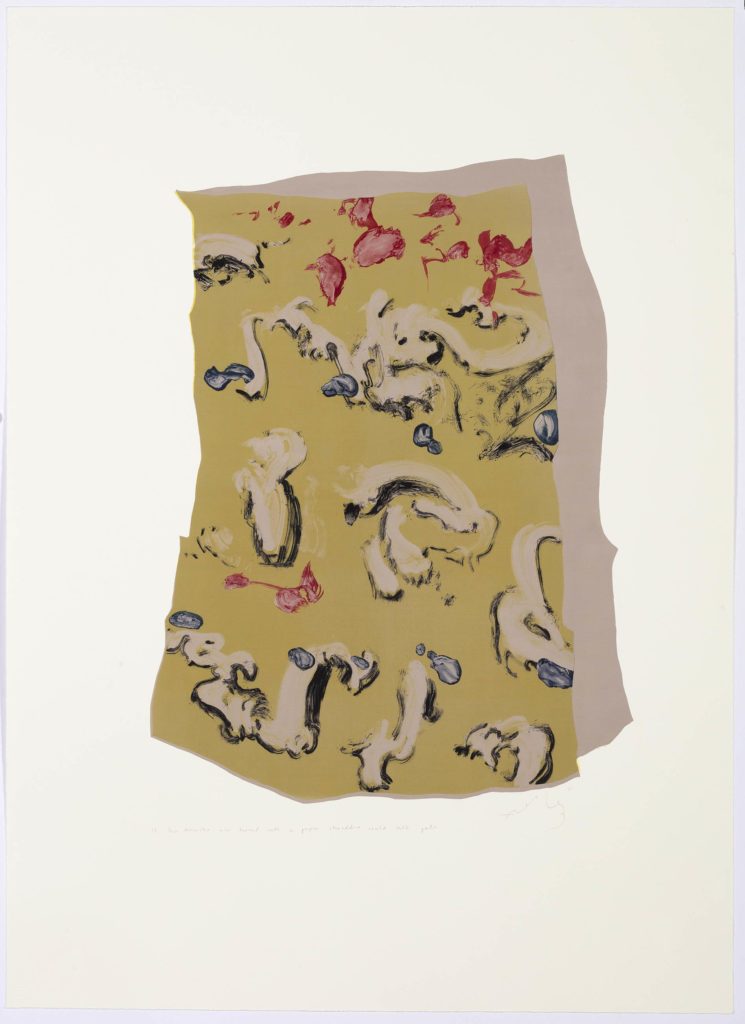

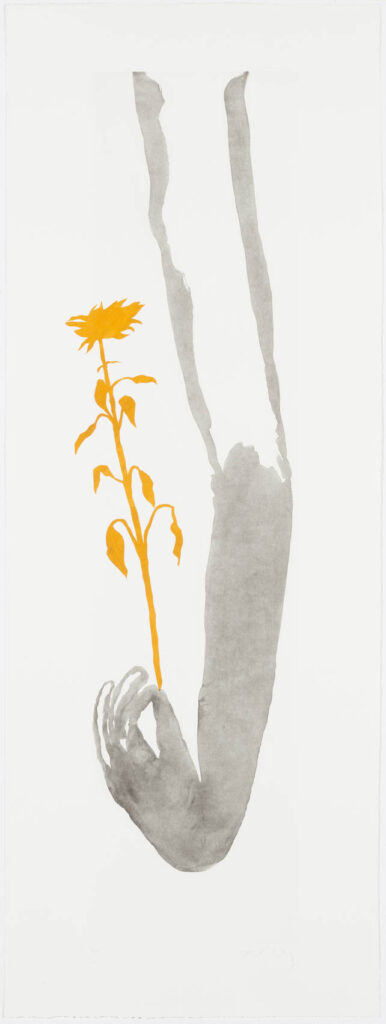

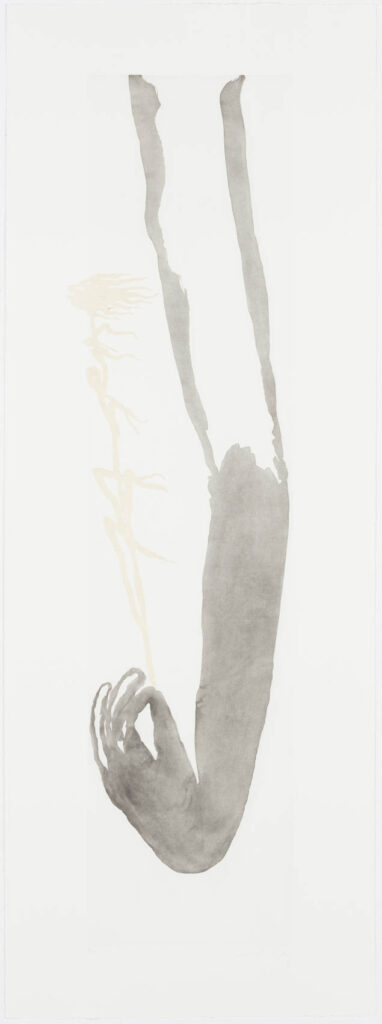

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 1/10

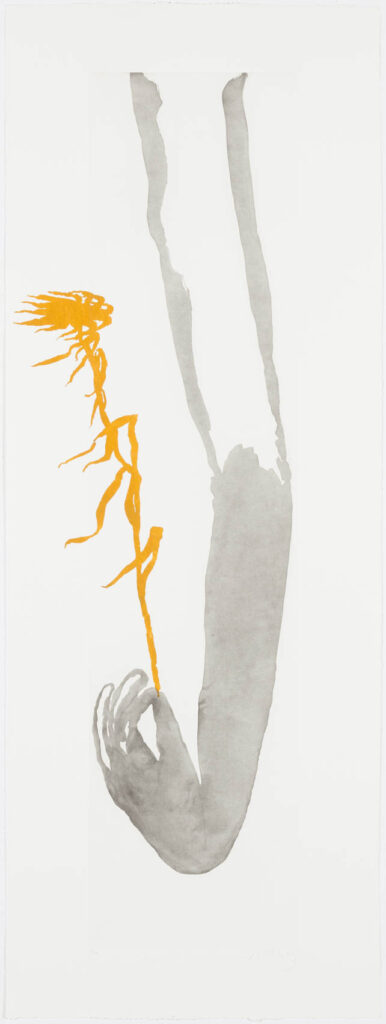

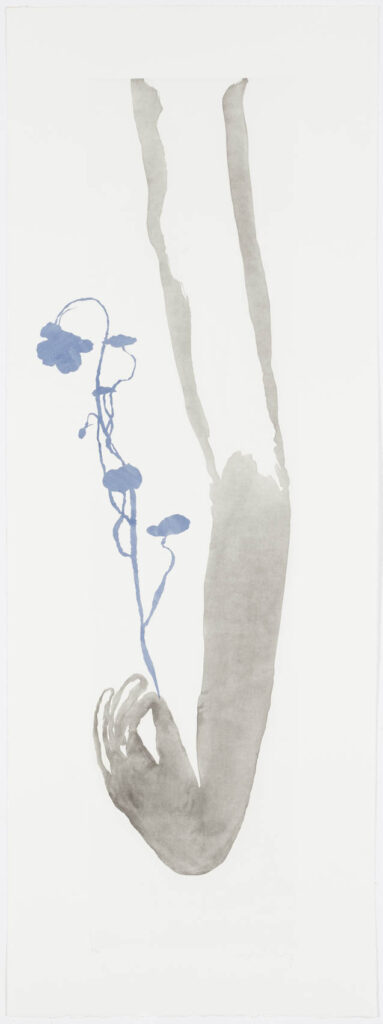

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 2/10

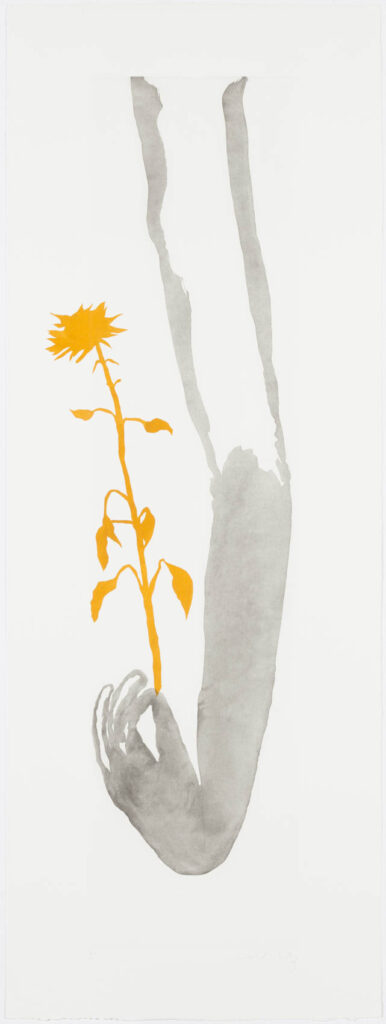

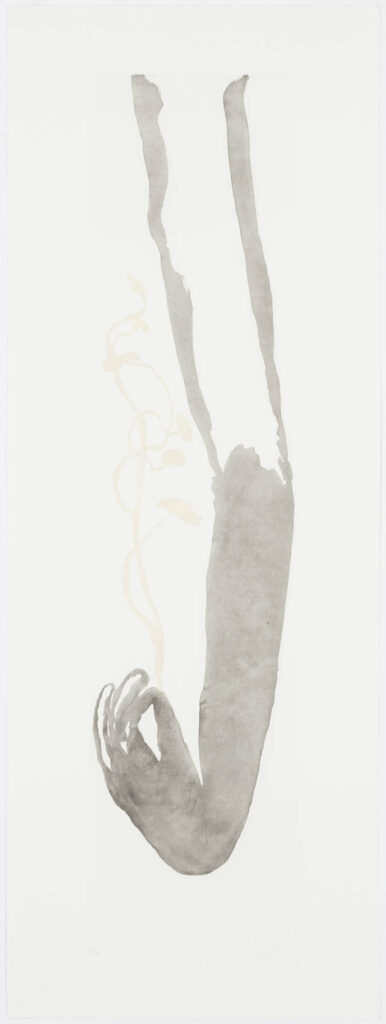

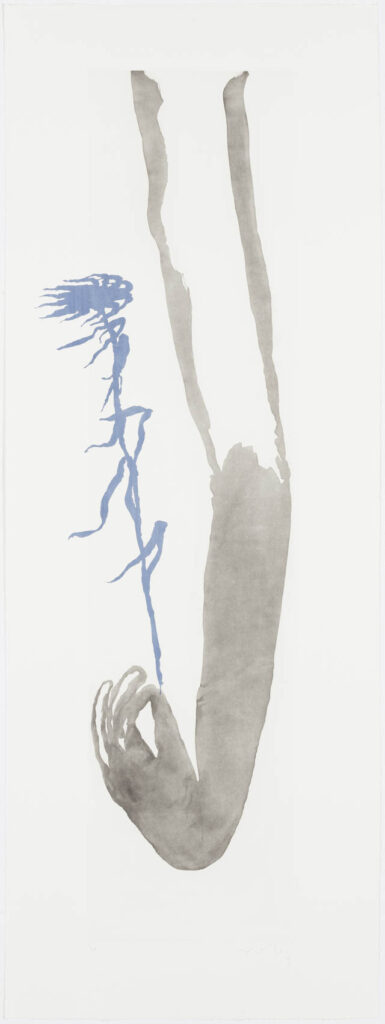

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 3/10

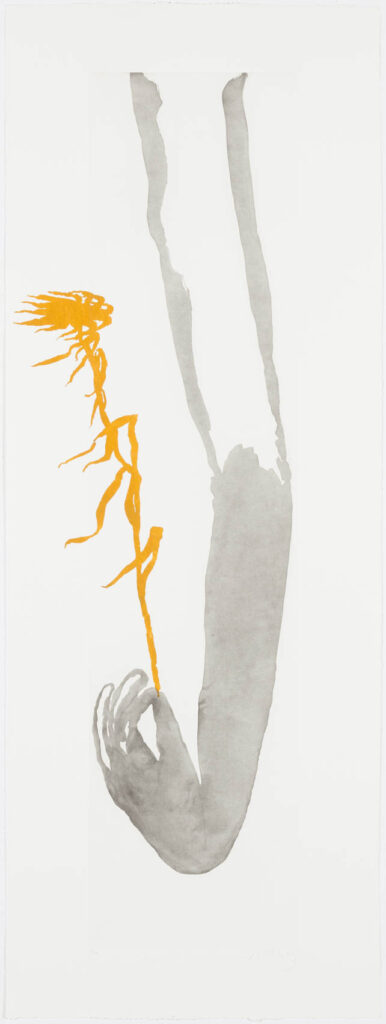

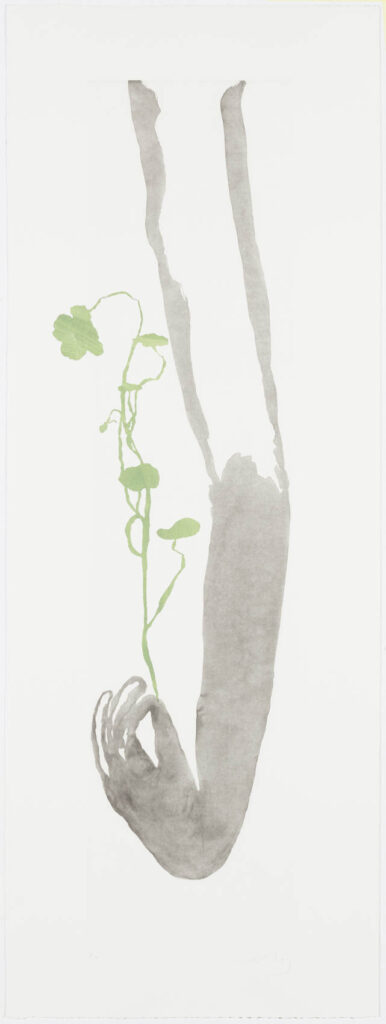

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 4/10

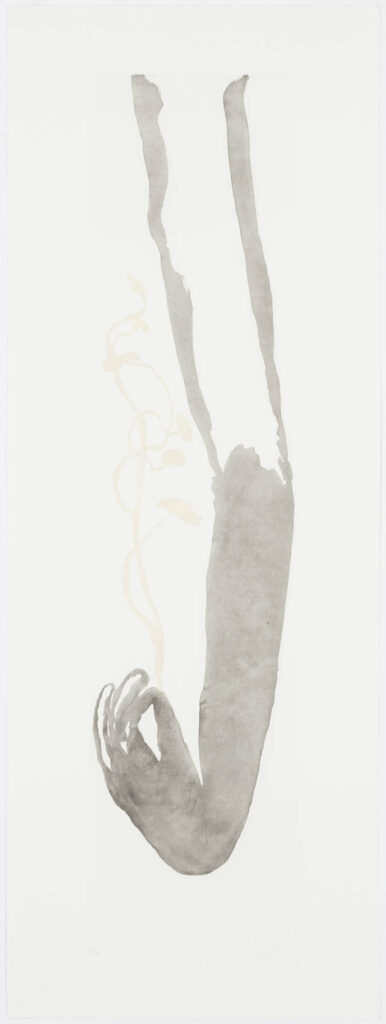

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 3/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 4/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 5/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 6/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 7/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 8/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 9/10

All the bugs in my garden know your name

Liftground and spitbite acquatint with hand paint chine colle

104.4 x 36cm

Edition: 10/10

Anna van der Ploeg

Omens in hot bacon

contradiction

Words and actions; two impulses separated into two feet – you are suddenly pushed from behind. Which foot steps forward to catch you? Your left foot is tied to the chair leg.

David Krut Projects is pleased to present Omens in hot bacon contradiction, a new body of work by Anna van der Ploeg. The unassuming table has long been the subject of Van der Ploeg’s work; through oil paintings, sculptural woodblocks, etching editions and unique paintings on paper, this innocent object of functionality and site of bounty and beauty in art history is brought into a disquieting arena of dinner table talk and capricious human interactions.

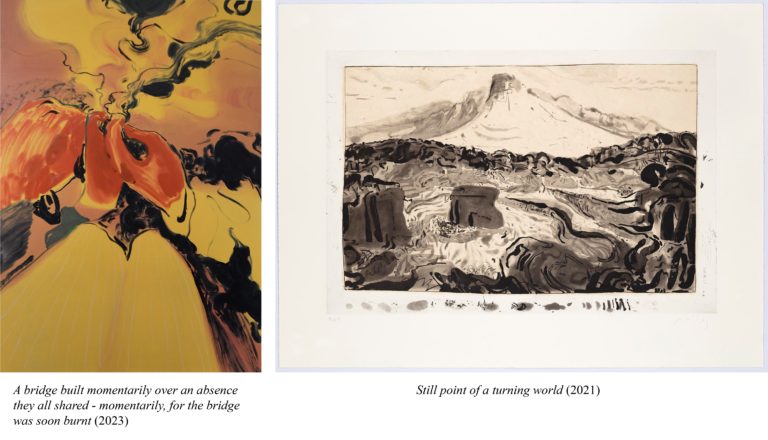

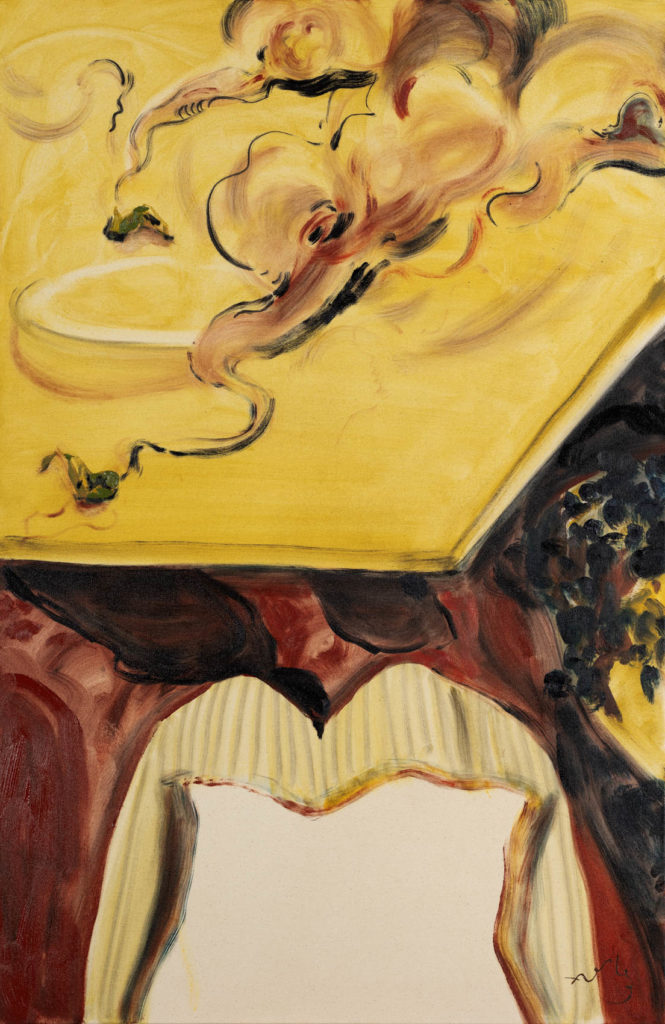

A bridge built momentarily over an absence they all shared – momentarily, for the bridge was soon burnt, 2023

Oil on canvas

53.2 x 37.6 in / 135 x 95.5 cm

Available in New York (inquire for shipping cost)

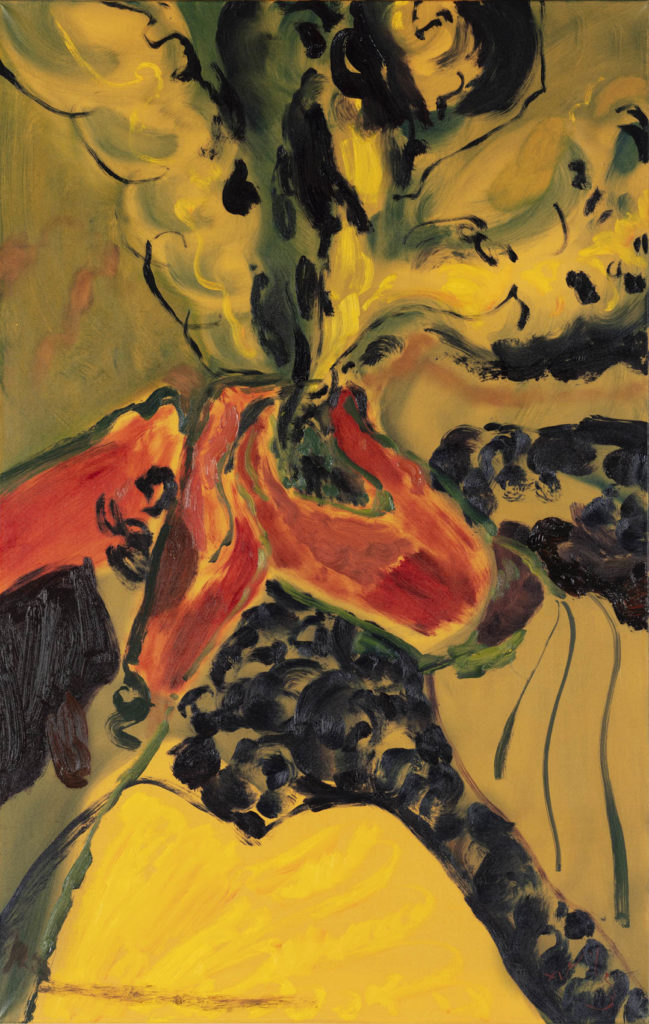

Over and over in later years when she told this story she marvelled at his ability to eviscerate coincidence, 2023

Oil on canvas

39.4 x 22.4 in / 100 x 57 cm

Available in New York (inquire for shipping cost)

Editions

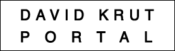

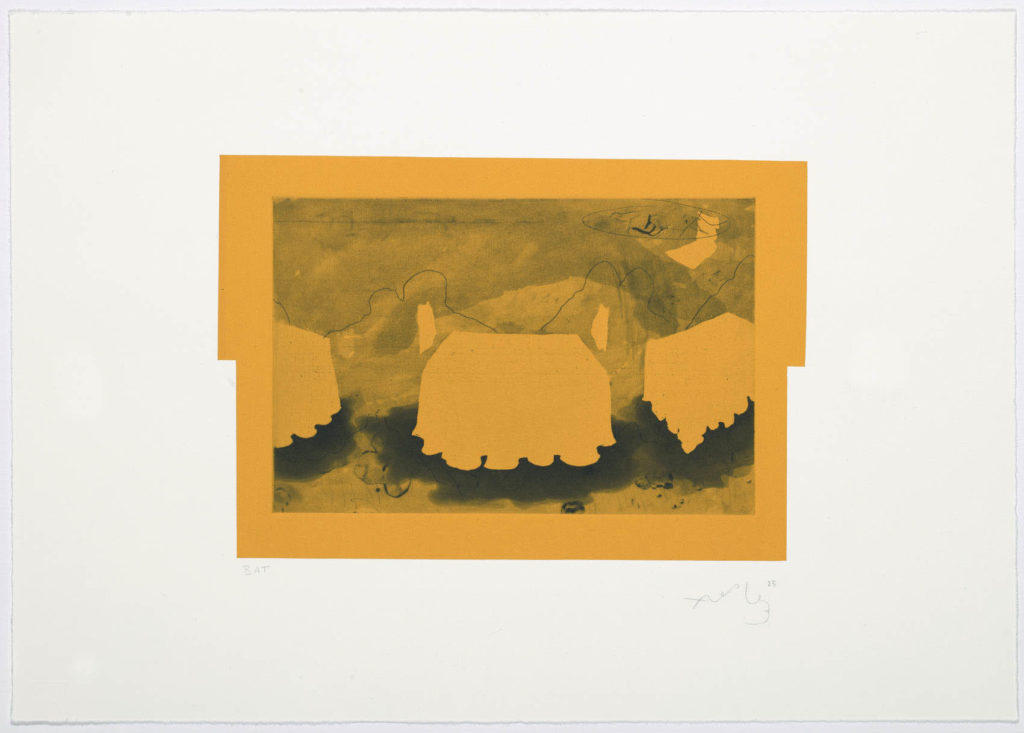

The negotiators (2021)

Liftground and spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint

Edition of 15

65,4 x 101,4 cm

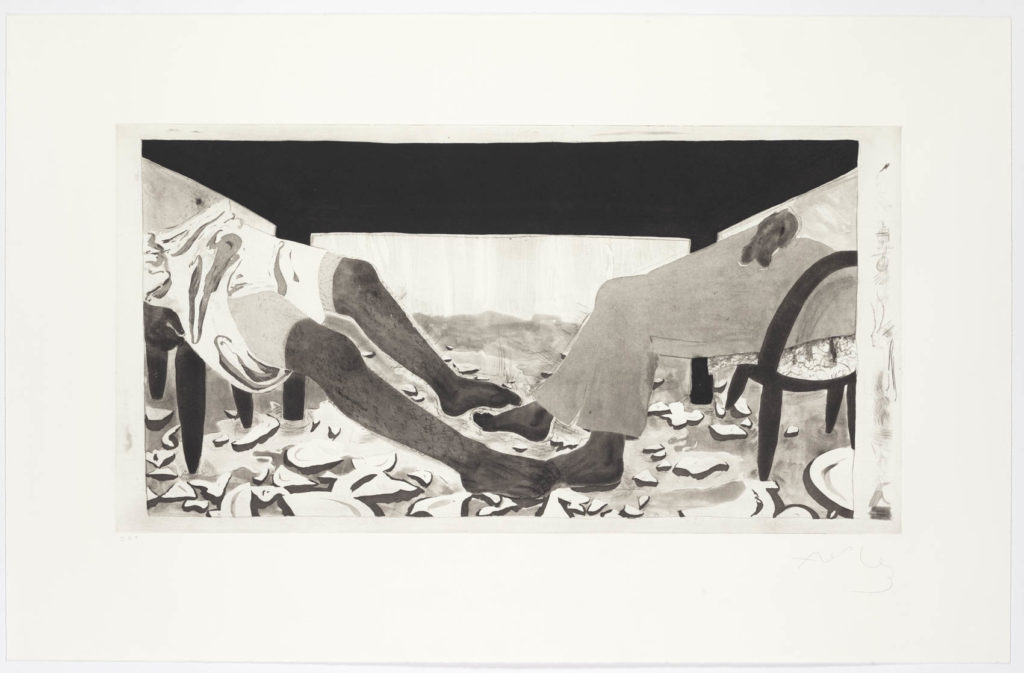

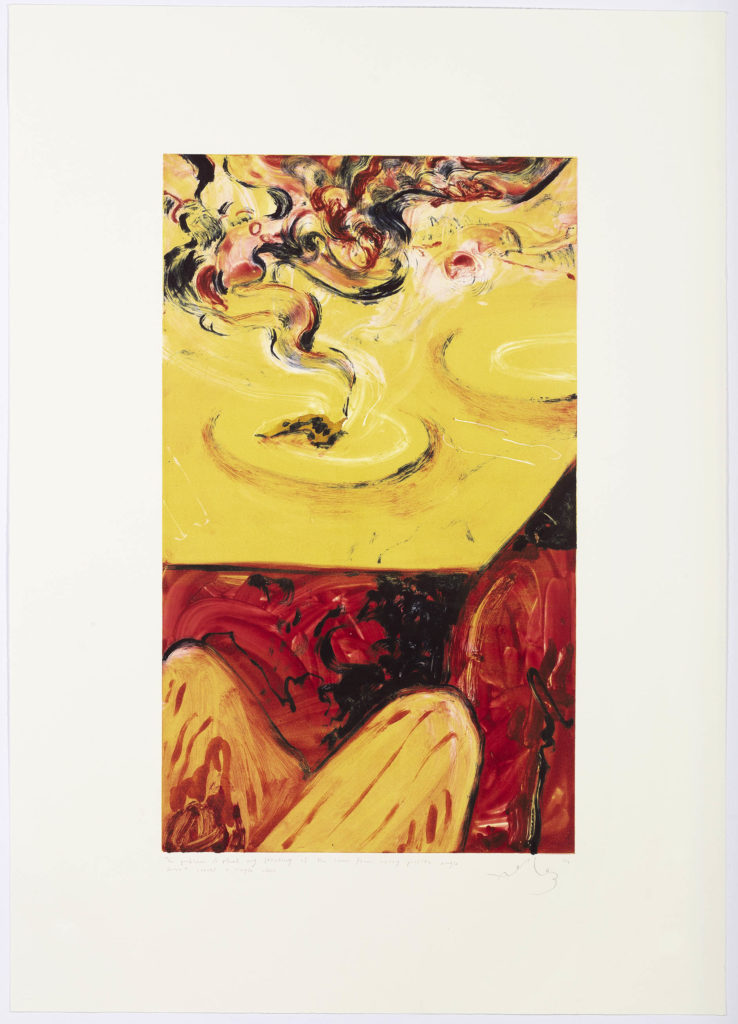

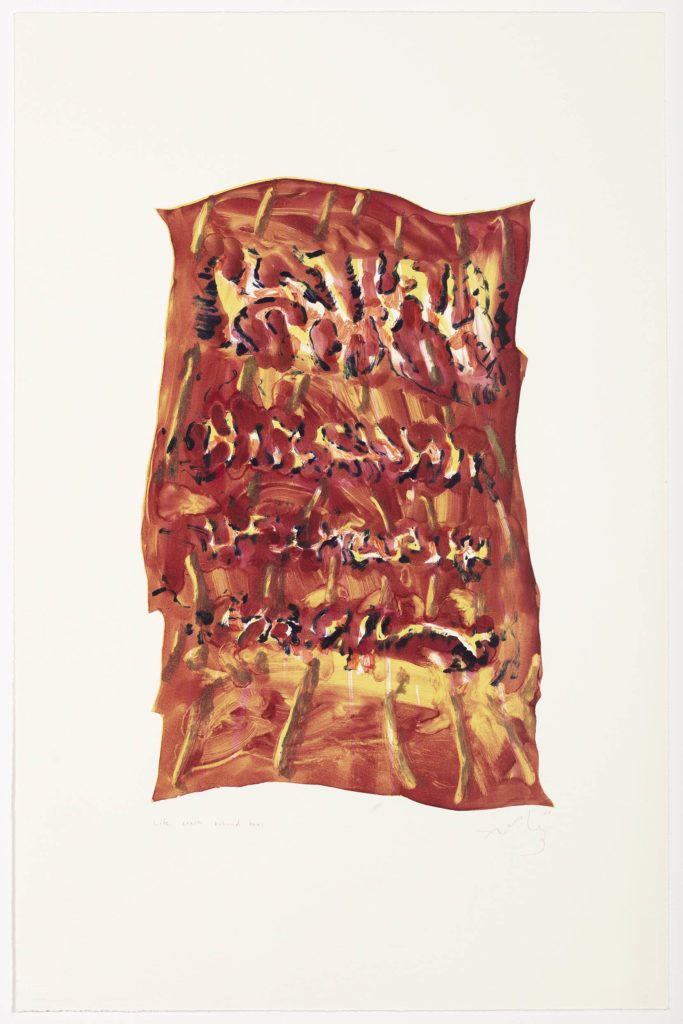

That hot bacon smell of pure

contradiction (2023)

Hardground, liftground and spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint

Edition of 18

65.4 x 101.4 cm

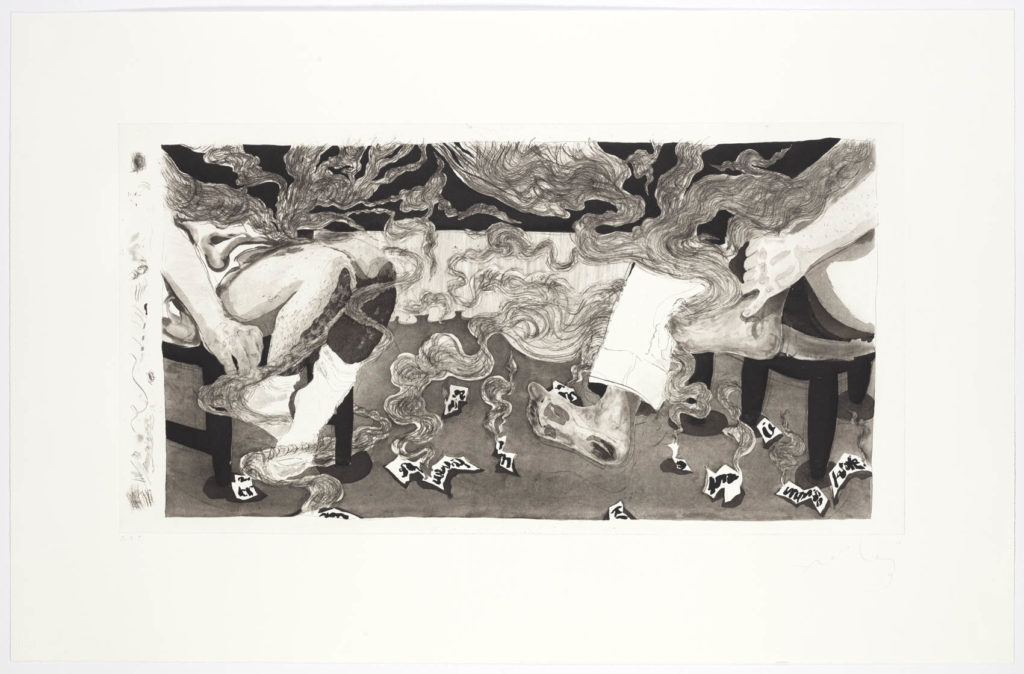

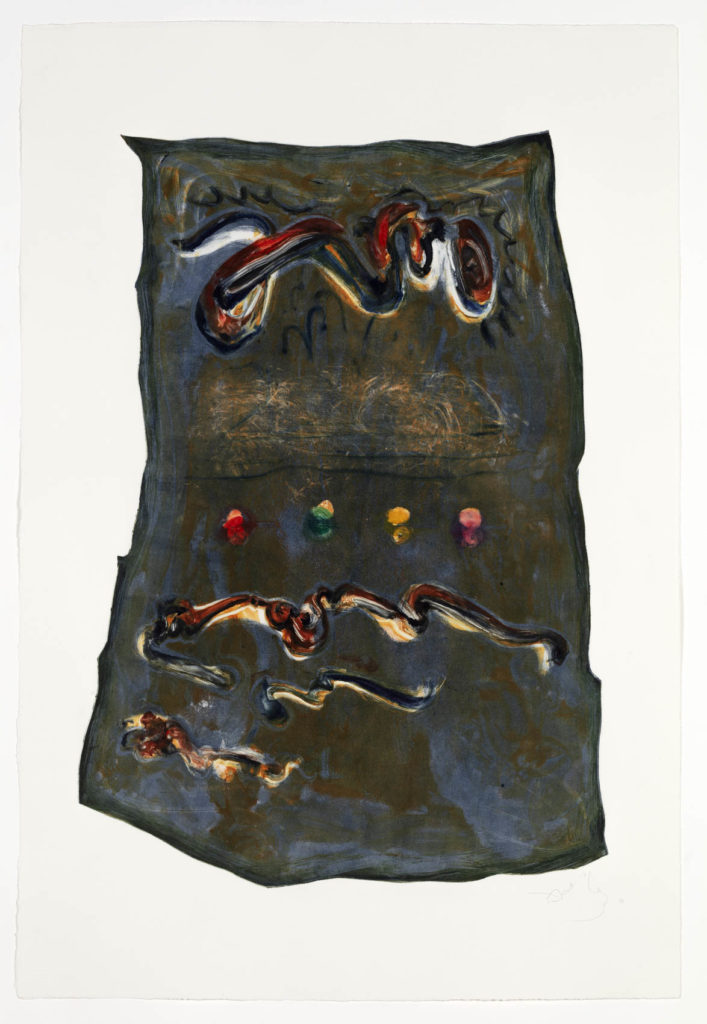

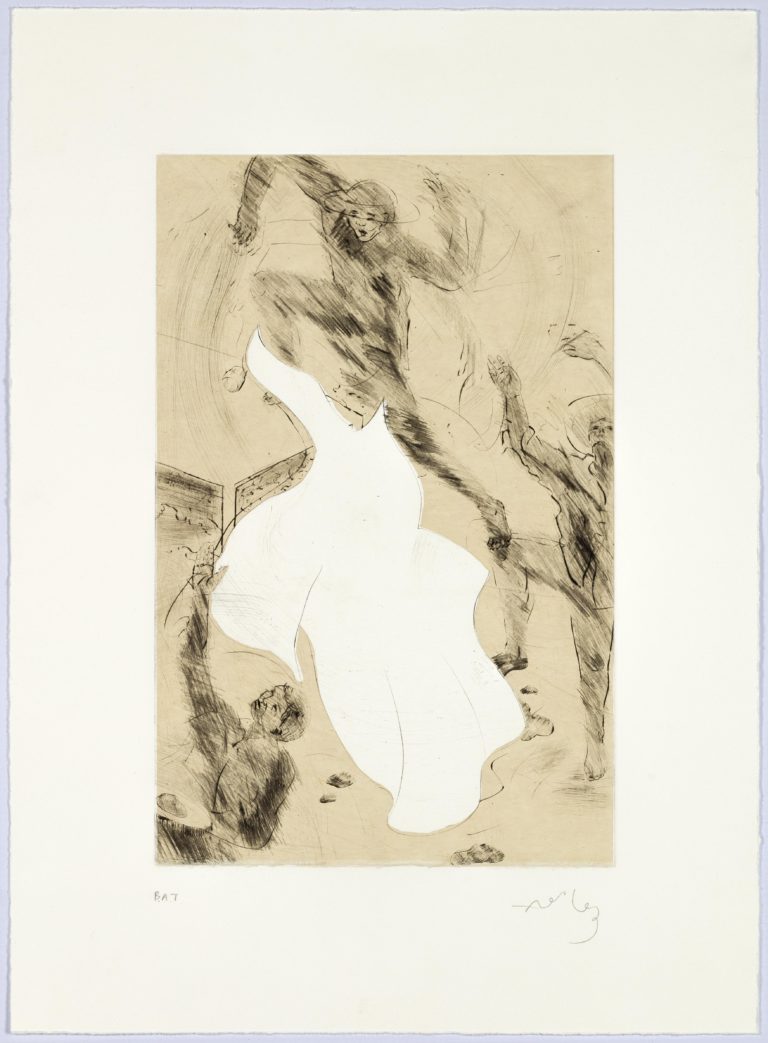

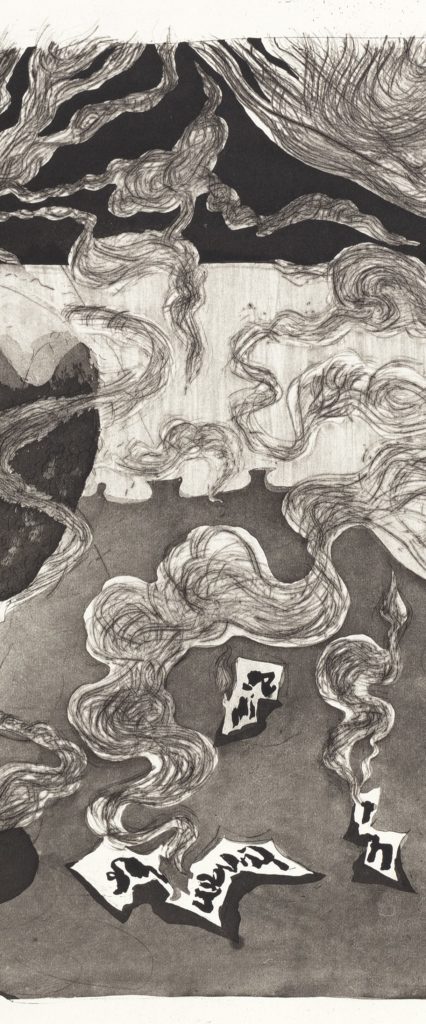

Antilogic is the dance of the dog in hell happy to eat any food that grows, but do they not say the same of a dog in heaven? (2023)

Hardground, liftground and spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint

Edition of 18

65.4 x 101.4 cm

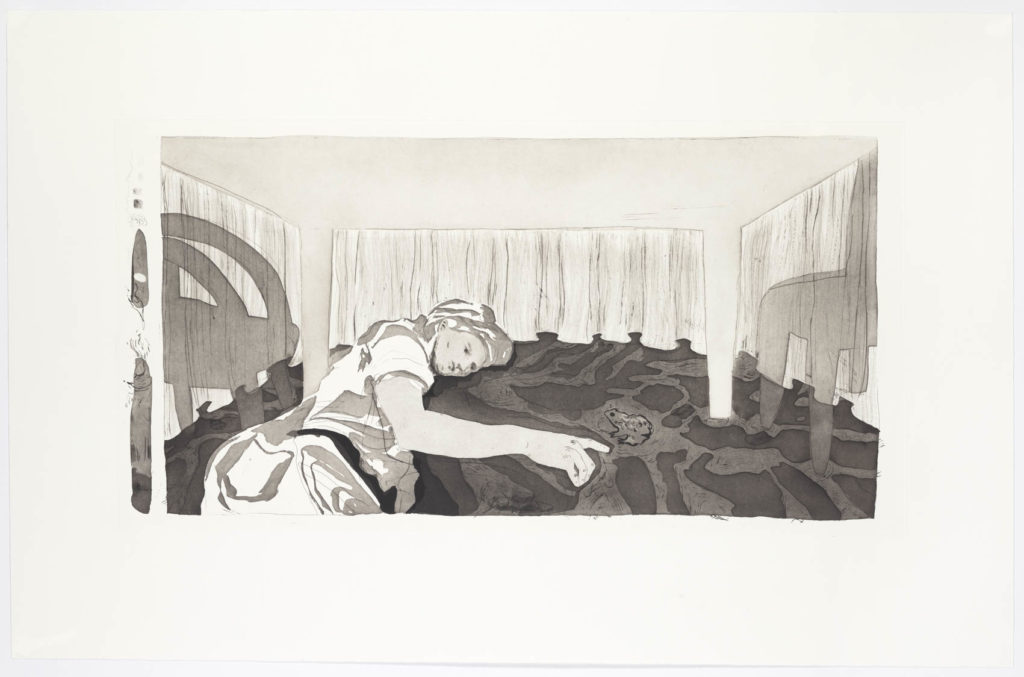

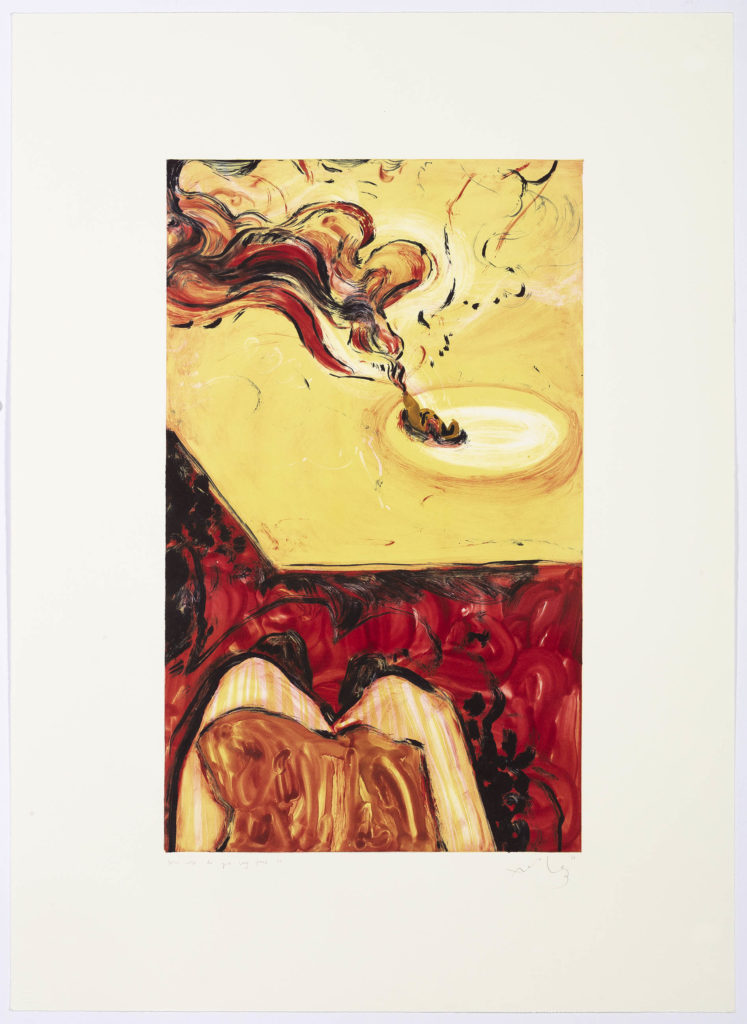

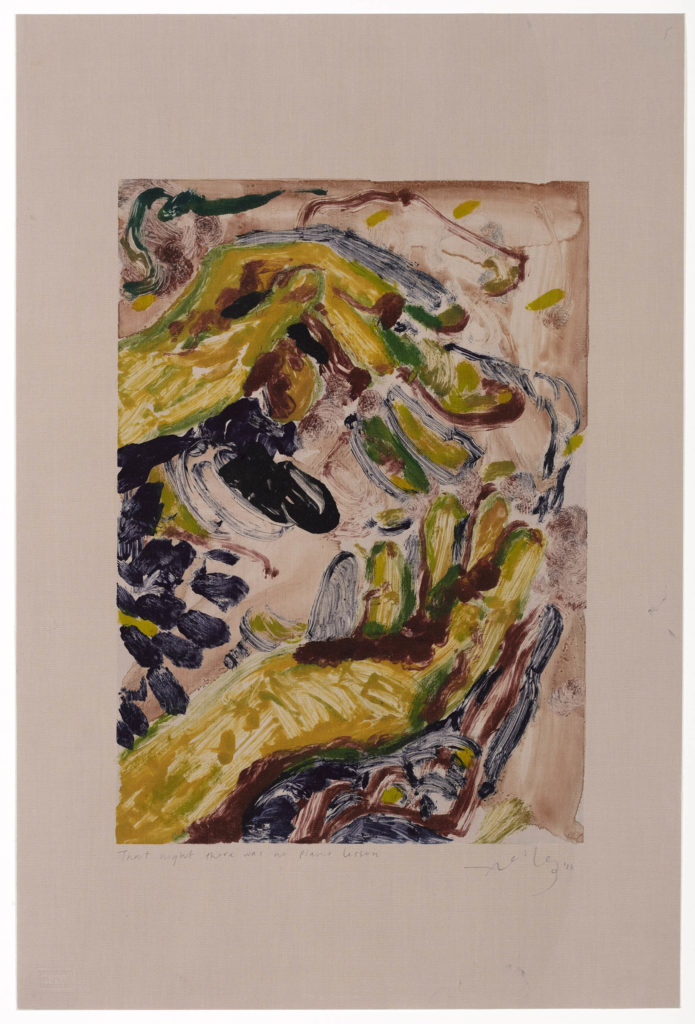

Yes I heard you thinking of me did you hear me laughing (2023)

Hardground, liftground and spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint

Edition of 18

65.4 x 101.4 cm

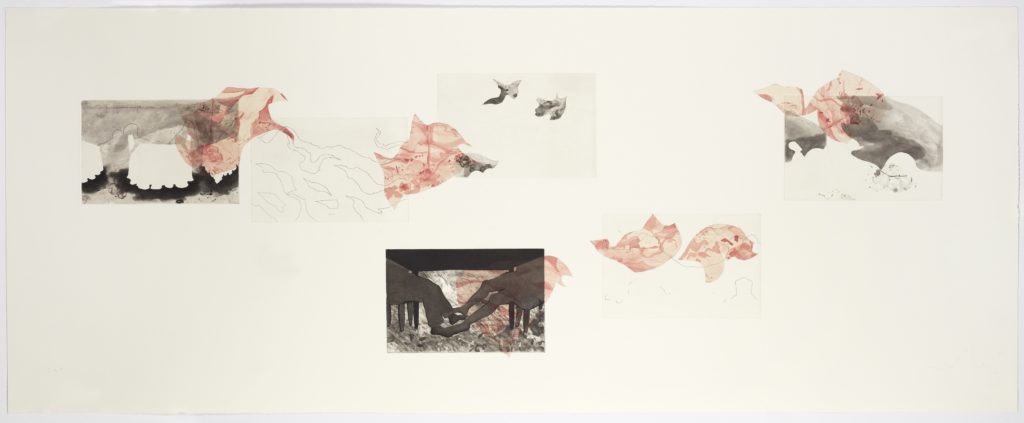

No date no wait no fate to contemplate (2023)

Liftground with drypoint, liftground, spitbite aquatint printed chine collé

Edition of 7

141,5 x 56 cm

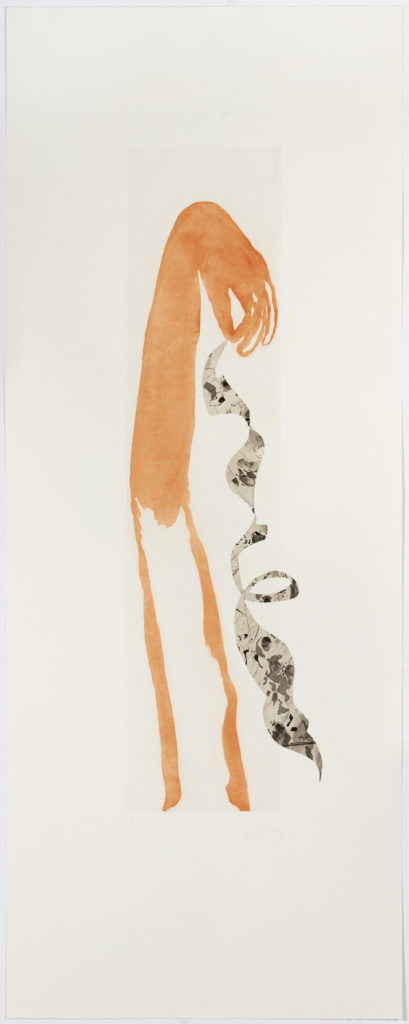

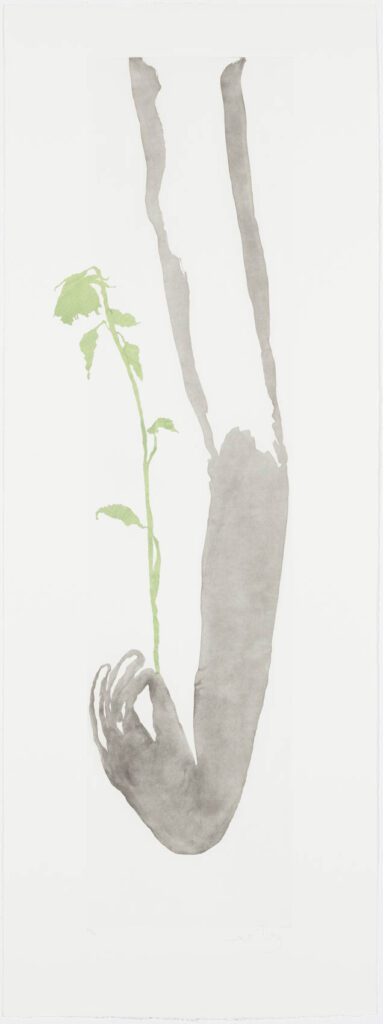

Omens are for example hearing someone say victory as they pass you in the street (2023)

Liftground with drypoint, liftground, spitbite aquatint printed chine collé

Edition of 7

141,5 x 56 cm

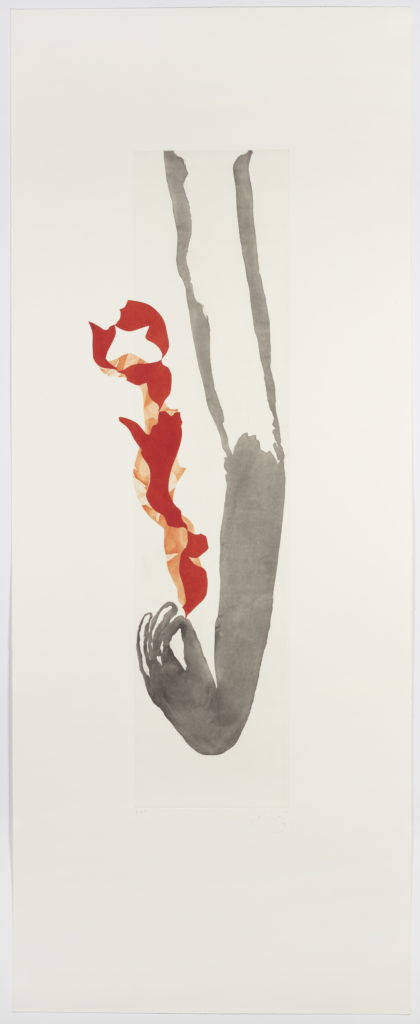

Possible night, impossible night, pegs, strings, stringing one excuse to every guest (2023)

Hardground, liftground, spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint and chine collé

Edition of 7

141,5 x 56 cm

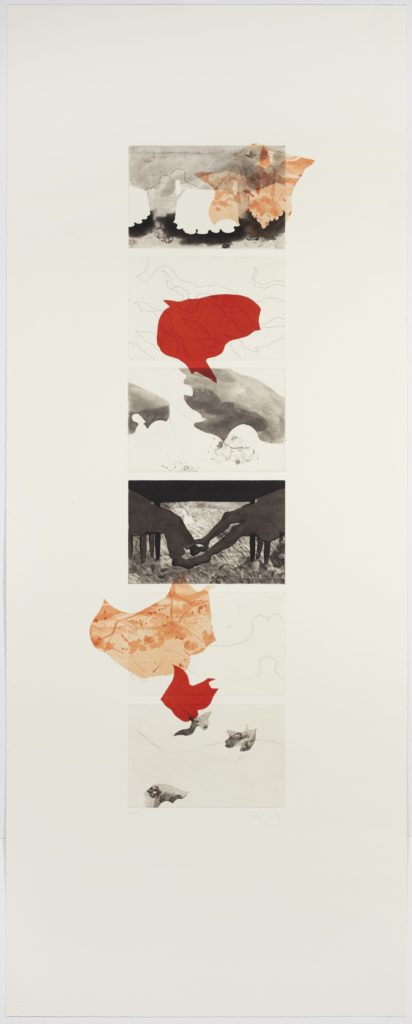

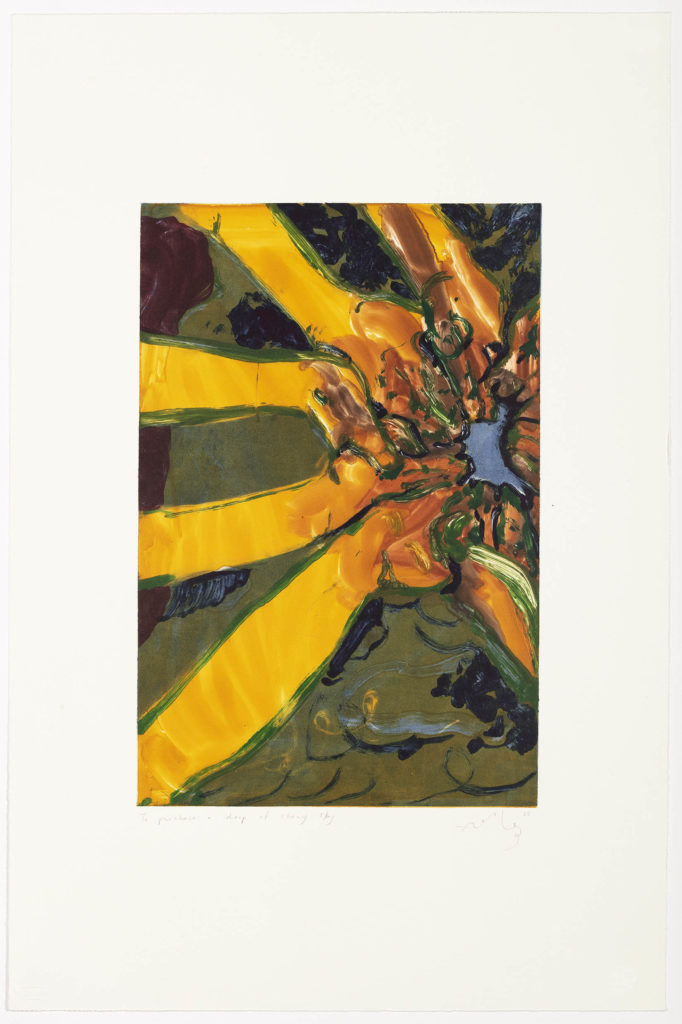

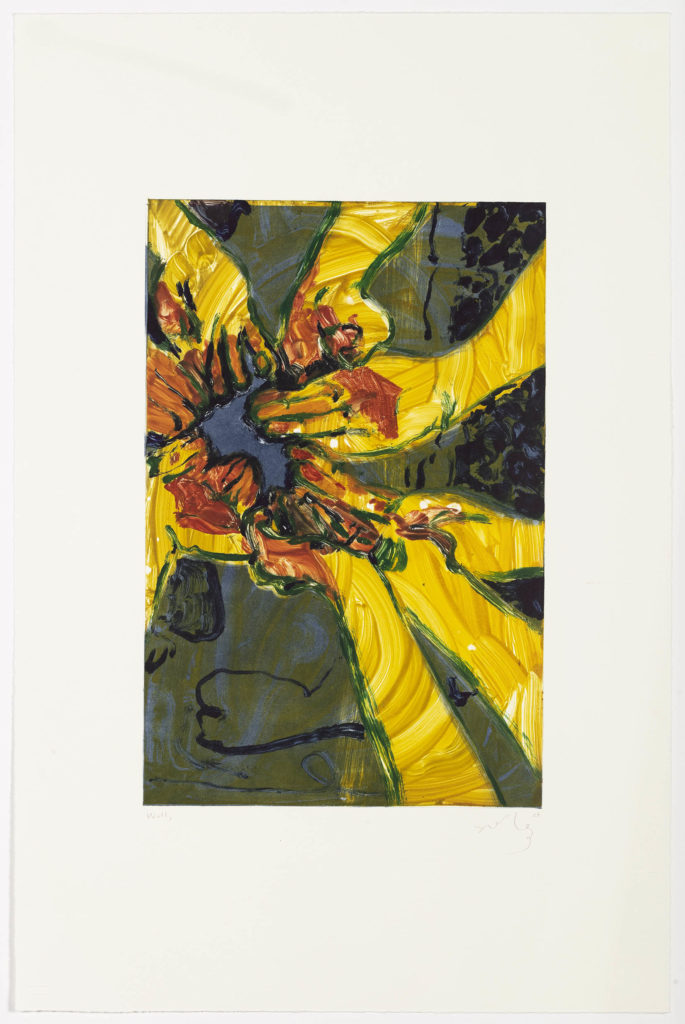

What eyes at eagle height can see back as far as a day in March (2023)

Hardground, liftground, spitbite aquatint etching with drypoint and chine collé

Edition of 7

56 x 141,5 cm

I’ve relived that moment many times since then, but in the last couple of years, I’ve started to imagine it from a third point of view (2023)

Liftground and spitbite aquatint, with drypoint on silkscreen coloured Hosho adhered to paper

Edition of 12

32.5 x 46 cm

Any informed spectator would have understood that scene (2023)

Spitbite aquatint and drypoint on silkscreen coloured Hosho adhered to paper

Edition of 12

32.5 x 46 cm

Monotypes

Unique paintings transferred using a press

Available in New York

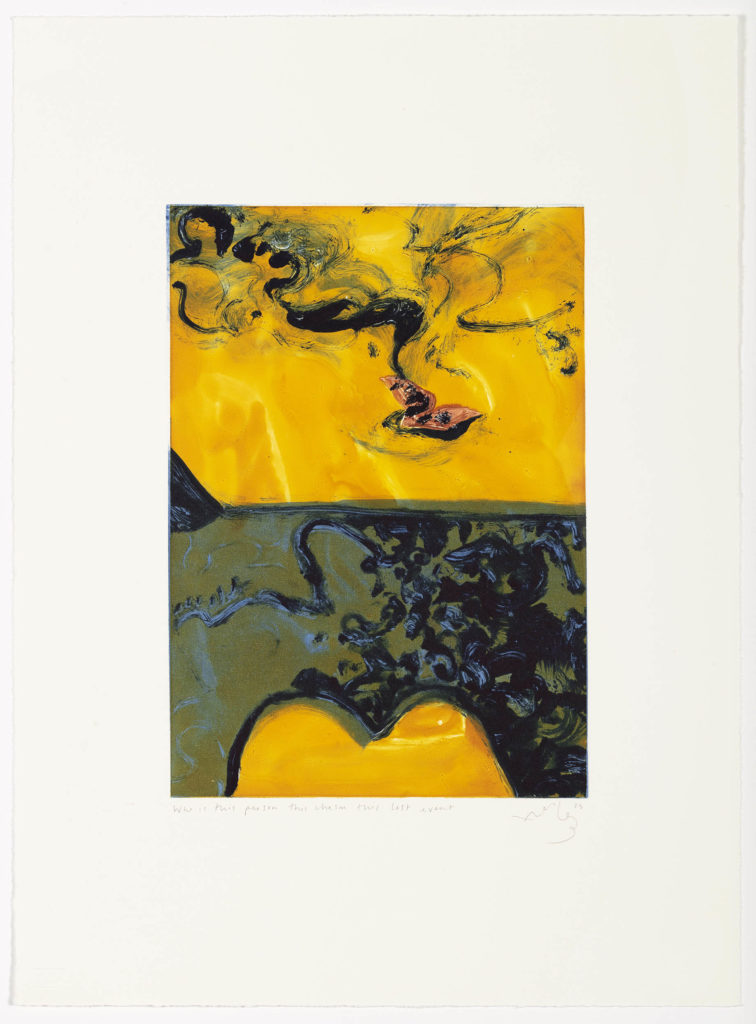

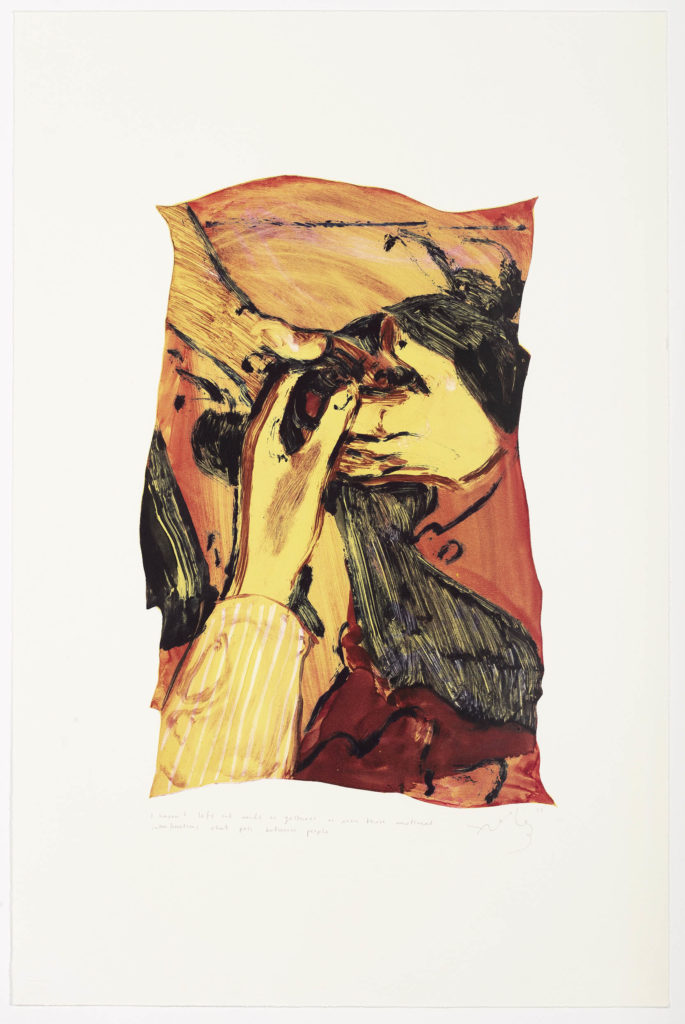

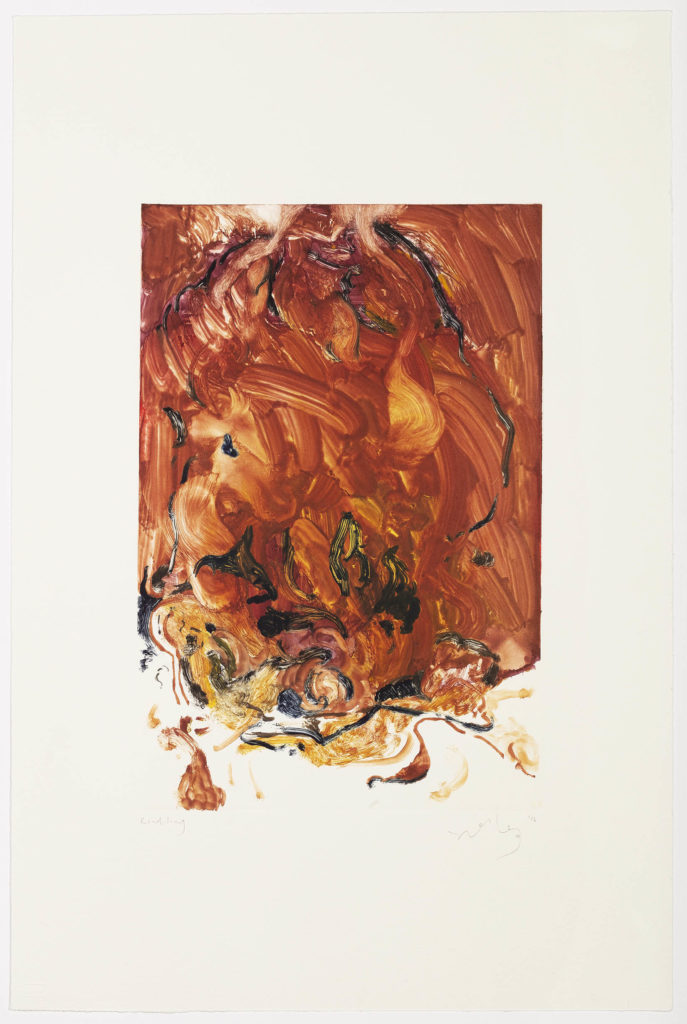

Who else do you say that to, 2023

Multi-layered oil-based monotype

39.4 x 28.3 in / 100 x 72 cm

The problem is that my scrutiny of the scene from every possible angle doesn’t reveal a single clue, 2023

Multi-layered oil-based monotype

39.4 x 28.3 in / 100 x 72 cm

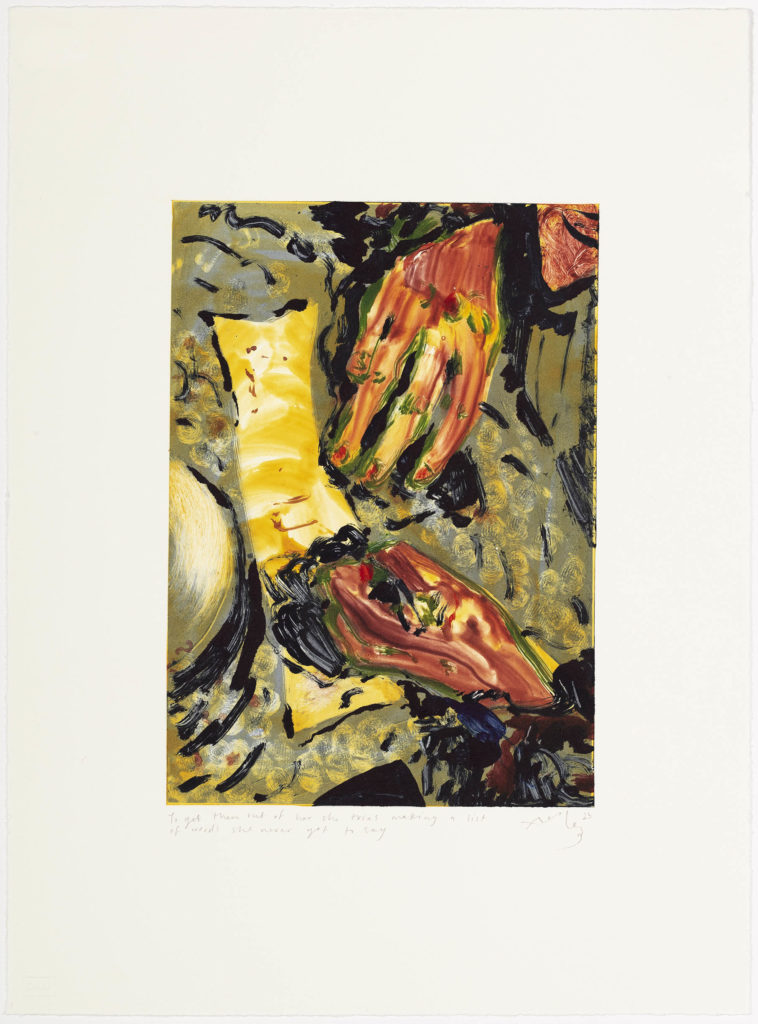

To get them out of her she tries making a list of words she never got to say, 2023

Multi-layered oil-based monotype

19.3 x 14.2 in / 49 x 36 cm

Monotypes Available in Johannesburg

Fiction forms what streams in us

Oil painting on canvas

100 x 72 cm

Available in Johannesburg (inquire for shipping cost)

Detail as a reticent event

Oil painting on canvas

100 x 72 cm

Available in Johannesburg (inquire for shipping cost)

A bracket’s worth of mirage

Oil painting on cotton

94 x 60 cm

Available in Johannesburg (inquire for shipping cost)

Enter the drinkable thread of life

Oil painting on cotton

94 x 60 cm

Available in Johannesburg (inquire for shipping cost)

Anna van der Ploeg: Unusual Constraints

Kate McCrickard

June 2023

When I arrive in her studio in the attractive town of Leuven, a short train ride south of Brussels, one of the first remarks South African artist Anna van der Ploeg makes is a comment on restlessness: she needs room to roam – in her mind, all over the world and in her studio. Van der Ploeg has left her homeland temporarily and is, for now, happily settled in Belgium. The group of prints created with master printer Roxy Kaczmarek earlier in the year at the David Krut workshop in Johannesburg, form the basis of Omens in Hot Bacon Contradiction, her first solo show in New York. In a two-room studio – all industrial high windows and clear light – lodged in the handsome old factory building belonging to the M Leuven (Museum Leuven) Cas–co five-month residency, Van der Ploeg is finalising works to complete her New York show and for the exhibition required by the Museum at the end of her stay. She is working in varied media – oil painting, steam-bent plywood sculpture and printmaking in monotype and intaglio. Poetry, musings and the written word are also intrinsic to her practice; performative, kinetic ideas and floor-based sculptures may edge in too.

For the contiguous exhibitions taking place at David Krut 151 Gallery, Johannesburg and David Krut Projects New York, Van der Ploeg has devised works under the loose aegis of an unknown ‘game’: her images circle around ideas of board games, washing flapping on lines, hands holding tiny pools of space; hands holding wisps of paper set alight in twists of smoke like rising wishes; feet misaligned in the secret space under a table; a dialogue with a frog in that same safe space under the table. She gives us private views of knees seen from above and feet seen from below, setting up arenas of purported domestic calm. Van der Ploeg has an uncomfortable talent for sizing up the tacit truths played out in small human interactions.

How Do We Catch Smoke With our Hands?

Lukanyo Mbanga

June 2023

How do we catch smoke with our hands? How do we create a cocoon with our fingers to trap the transient heat? What weight do words hold if they can be turned to ashes in a single flame? Anna Van der Ploeg’s solo exhibition Omens in hot bacon contradiction is one that only leaves us with questions. The scenes are uncomfortably intimate, inviting the audience to act as witnesses whilst simultaneously expelling us to the side-lines. There is nothing more confrontational than subjective realism. That nullifying feeling of, “it makes sense, but it also doesn’t.” I’ve tried to make sense of it and only realized that like all art, how we interact with it will always be nuanced with our own understandings of shapes, things, and experiences.

Van der Ploeg’s work is strangely reminiscent of Blake and Beckett. It’s a bizarre connection and a strange mix of eras but the connection is apt, nonetheless. We see William Blake in the mystical representation of the human form, the contained earthy and intestinal colour-palate, as well as the interdependent relationship between words and image. A Beckettian air emerges in the reduction of the body, as well as the absurd and interrogative question that calls us to “imagine” as we gaze at a woman laying languidly beneath a table seemingly conversing with a frog (See Yes, I heard you thinking of me did you hear me laughing). Through this, we see how The Romanticist and Modernist converge as Van der Ploeg draws on the subjective experience of human exchange with representational rather than realistic forms. It calls us to witness an ineffable realm of human interaction made solid with etched marks and brushstrokes.

Workshop Residency Blogs